Dylan K. Picart

Surveys are the pulse of human data, especially across schools, nonprofits, community programs, and municipalities. But anyone who’s wrangled survey responses knows the chaos: inconsistent headers, multilingual answers, unlinked IDs, and years of drift between forms.

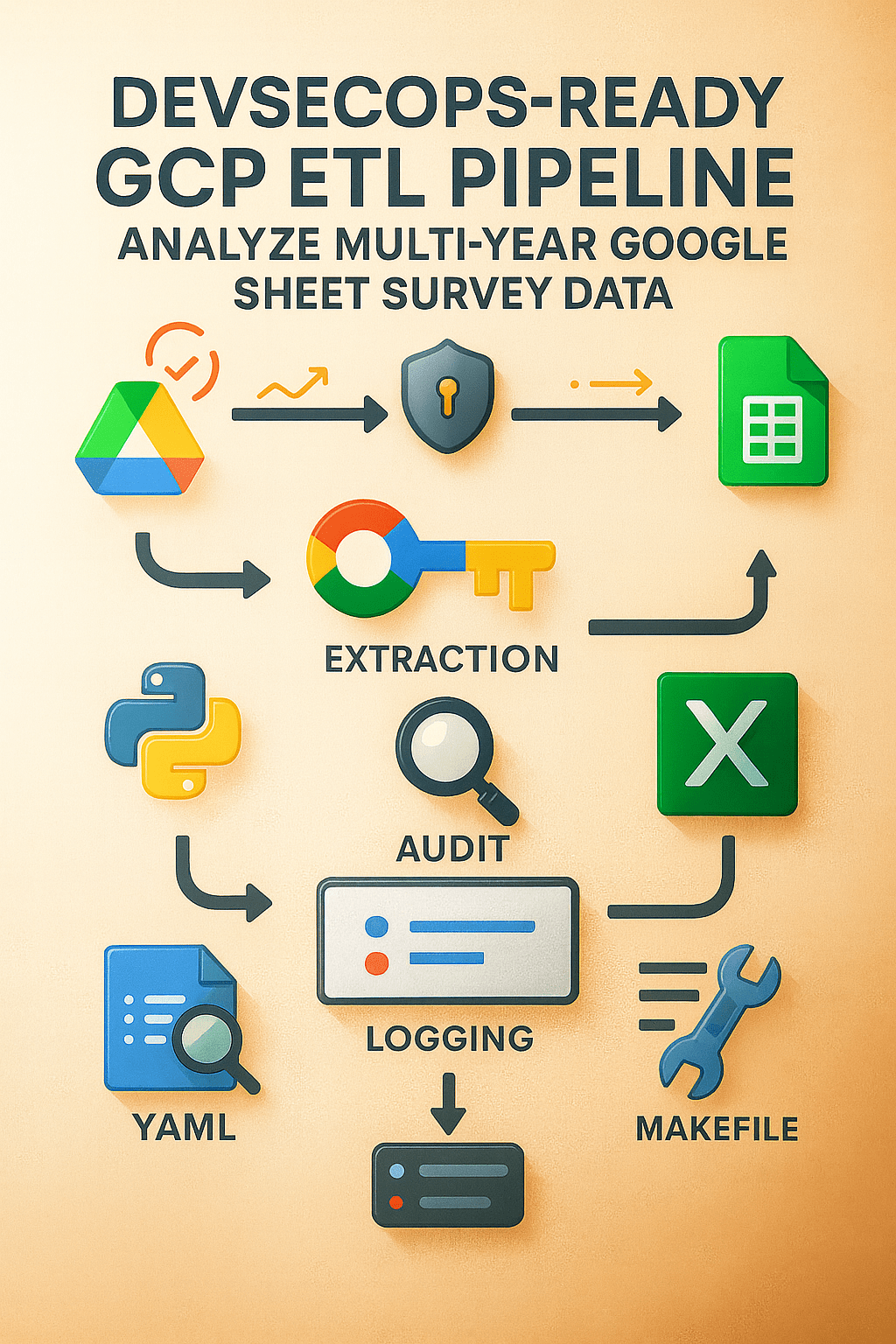

I built this pipeline inline with the same intention of my Multilingual ETL Pipeline: To turn that chaos into clarity — transforming hundreds of Google Sheet Surveys across years and languages into a harmonized, analytics-ready dataset that can feed dashboards, reports, or machine-learning models.

This wasn’t just another Python project; it was a surprisingly complex ETL pipeline, derived from lessons that included my NYC InfoHub Scraper package to VBA Automations and beyond, designed with security, reproducibility, and maintainability at its core.

The Challenge: From Manual Downloads to Reproducible Pipelines

Before this pipeline, analysts spent hours manually exporting hundreds of CSVs from Google Sheets across years, renaming columns, and combining them in Excel. It was error-prone and impossible to reproduce consistently.

The goal was clear:

- Automate data retrieval using Google Drive and Sheets APIs

- Centralize YAML-based configurations for consistency

- Enforce DevSecOps standards for auditing, testing, and code quality

- Deliver Excel outputs that executives can use immediately

Architectural Overview

root/

├── scripts/

│ ├── extract/ # API calls, CSV scraping, cleaning

│ ├── transform/ # Normalization, translation, mapping

│ └── load/ # Consolidation and Excel export

├── data/

│ ├── raw/ # Unprocessed CSVs

│ ├── configs/ # YAML mappings, canonical questions

│ └── processed/ # Cleaned + summarized data

├── logs/ # Phase-wise logs for QA

├── Makefile # One-command orchestration

├── SECURITY.md # Security policy & disclosure guidelines

└── tests/ # Unit tests + pipeline QA

Every directory serves a purpose, and every step is traceable through structured logs.

If something fails, the log hierarchy points to exactly where and why — keeping debugging quick and reliable.

Step 1: Extract — Securely Mapping and Pulling Data from Google Drive

The pipeline’s first task is to build a complete, authoritative map of the survey ecosystem across all academic years, cohorts, and languages. Since every dataset lived inside Google Drive and Google Sheets, I needed an extraction layer that could do far more than download individual files. It had to authenticate securely, explore folder structures programmatically, and capture metadata for hundreds of survey tabs without manual intervention. This is where Google Cloud Platform (GCP) played a central role.

To support full automation, I configured a dedicated GCP project and enabled the Google Drive and Google Sheets APIs. I then created a service account with tightly scoped, read-only permissions. Unlike my earlier Multilingual ETL Pipeline, this credential replaces all human authentication. The pipeline now authenticates directly through the service account, running fully unattended while still respecting GCP’s IAM boundaries.

With GCP authentication in place, the extractor (scrape_drive_links.py) uses Google’s Python client libraries to:

- Traverse the Drive hierarchy for each academic year

- Locate each “Student Feedback” folder

- Identify school-level subfolders

- Determine whether each file belongs to the older or younger cohort

- Enumerate all tabs in every spreadsheet through the Sheets API

- Capture each tab’s unique

gid,sheet_id, and tab name

Instead of relying on naming conventions or manual link tracking, the script uses API metadata to understand the actual structure of the Drive. This makes the extraction resilient to renamed files, reorganized folders, or newly added surveys.

To ensure long-running jobs remain stable, the extractor uses exponential backoff for Drive or Sheets API rate limits. When errors like 403, 429, or 503 occur, the script waits progressively longer before retrying, preventing quota exhaustion and guaranteeing that the run completes without manual babysitting.

Environment variables stored in .env tie everything together:

GOOGLE_APPLICATION_CREDENTIALS=creds/service_account.json

ROOT_FOLDER_ID=<drive_root_id>

By combining these components — a GCP service account, Drive and Sheets APIs, and robust error handling — the pipeline gains a secure, cloud-managed foundation for every downstream step. Each extract run begins with the most current, authoritative survey structure, which is automatically written into a central configuration file (links.yaml) for the rest of the ETL to use.

This architecture turns what used to be a fragile, manual task into a reliable extraction service that evolves naturally as the data landscape changes.

YAML as the Foundation of Consistency

I was first introduced to YAML by the Director of Engineering at Annalect, who showed me how configuration-driven design can transform data infrastructure. Before that, I kept most configuration inside Python dictionaries: mappings, column sets, parameters, and paths all lived in code. It worked, but every small change meant touching Python files, risking regressions, and redeploying.

YAML changed that. It offers the same expressive power as a Python dictionary, but lives outside the codebase:

# In Python

question_map = {"Q1": "Engagement", "Q2": "Satisfaction"}

# In YAML

question_map:

Q1: Engagement

Q2: Satisfaction

That separation matters. YAML is human-readable, easy to version-control, and safe for analysts to edit without writing Python. In this pipeline, YAML became the backbone of both extraction and transformation.

How YAML Powers the Pipeline

The auto-generated links.yaml file is the navigation blueprint for the entire ETL flow. It records, for each academic year and cohort:

- Which schools are present

- Which Google Sheets belong to each school

- Which tabs (and

gid/sheet_idpairs) hold the survey responses - How those tabs are categorized by level and language

Downstream, additional YAML configs in data/configs/ drive:

- Canonical question mappings

- Translation lookups for multilingual responses

- Standardization rules for survey scales and response buckets

Because these rules live in YAML rather than hardcoded logic:

- The system stays modular and maintainable

- New surveys, renamed tabs, or adjusted questions can be integrated by updating configuration, not rewriting code

- Data lineage from source sheet to final table remains transparent and auditable

Beyond This Single ETL

Over time, YAML has become a core part of my broader engineering stack. I use it to define Docker-based setups (docker-compose.yaml), service wiring, and environment variables for local and cloud deployments. It provides a common language for describing both data and infrastructure, which makes it easier to scale systems without losing clarity.

By combining automated generation of links.yaml with configuration-driven design, this project achieves something important: the pipeline stays synchronized continuously with reality. When new surveys appear, old ones evolve, or folder structures shift, the YAML updates and the code keeps working. That is the real power of YAML in this ETL: It turns a fragile collection of scripts into a living, adaptable system.

A Continuously Synchronized Extraction Layer

By combining automated Drive crawling, GCP-authenticated access, and YAML-driven configuration, the Extract stage achieves something powerful: it stays synchronized with reality. New surveys are discovered automatically. Renamed tabs are captured without intervention. Outdated links disappear naturally. The pipeline adapts as the data environment changes.

This approach reflects a core part of my engineering philosophy: leverage cloud identity, API-first design, and configuration-driven automation to build pipelines that are secure, scalable, and easy for teams to maintain.

Step 2: Transform: From Chaos to Canonical Form

Once extracted, the transformation scripts handle:

- Column normalization: stripping spaces, lowercasing headers

- Data cleaning: removing nulls, fixing encoding artifacts

- Translation: converting all Spanish responses into English equivalents

- Mapping: applying the YAML canonical mappings

- Aggregation: generating frequency tables and Likert summaries

Each script writes intermediate files to data/processed/, ensuring no data loss between steps.

If a run fails, you can resume precisely from the last successful checkpoint.

2.05. The Importance of Data Audits

Data audits are the foundation of reliability in this pipeline.

Before any transformation or aggregation occurs, every dataset undergoes a structured two-stage audit that ensures the questions, responses, and columns align across years, schools, and cohorts.

Stage 1: Discovery and Profiling (raw_audit.py)

The first audit stage is an exploratory pass that profiles all raw survey files—often hundreds of Google Sheet exports pulled from Drive. It identifies every unique question, compiles sample responses, and highlights structural inconsistencies like missing columns, renamed questions, or new response options.

Each discovered question is logged with real examples in an audit table. Those tables form the basis of canonical mapping, which ties variant question wordings (like

“Do you feel safe at school?” vs. “How safe do you feel in your school environment?”) to a shared analytical intent, such as “Feelings of Safety.”

This stage outputs two curated files—one for each cohort (“Older” and “Younger”)—that define the canonical questions and expected responses. These are your question blueprints, effectively teaching the pipeline what to expect and how to interpret incoming survey data.

Stage 2: Standardization and Enforcement (audit_map.py)

Once the canonical definitions are established, the second audit stage applies them to every raw dataset moving forward.

Here, audit_map.py acts as the schema enforcer:

- It categorizes each question into themes (e.g., School Climate, Teacher Feedback, Student Voice).

- It builds an accepted responses map from the audit files, turning each question’s response list (like

Yes|No|Maybe) into a whitelist of valid values. - It normalizes metadata—ensuring columns like School Year, Grade, and Tab are standardized even if their headers vary (e.g., “SY” → “School Year”).

- It then projects the cleaned dataset onto the canonical structure, keeping only those questions and values defined in the audit.

Invalid, unexpected, or misspelled responses are automatically filtered out. Columns with no valid data are dropped, and the final dataset emerges with uniform structure and semantics across every year and school.

Why It Matters

This two-step audit system does far more than catch errors—it builds institutional memory into your data pipeline.

It preserves how questions evolve over time, ensures cross-year comparability, and prevents schema drift from silently corrupting your longitudinal data.

Each audit also doubles as documentation: a transparent record of exactly how raw surveys are translated into analytics-ready datasets.

In short, these audits don’t just clean data—they codify trust in it.

Simplified Core Logic

# --- Fundamental audit pattern ---

def build_accepted_map(df):

"""Map each question to its allowed responses (e.g., 'Yes|No|Maybe')."""

return {

# For each raw question, split the Sample Responses "Yes|No|Maybe" into a set of allowed values

row["Raw Question"]: {

r.strip() for r in str(row["Sample Responses"]).split("|") if pd.notna(row["Sample Responses"])

}

for _, row in df.iterrows()

}

def build_output_dict(raw, canonical_cols, accepted_map):

"""Keep only valid responses and align columns to canonical questions."""

out = {}

for col in canonical_cols:

if col in raw.columns:

allowed = accepted_map.get(col)

series = raw[col].astype(str).str.strip()

# If 'allowed' is a non-empty set, enforce the whitelist; if empty set() or None, keep all values

out[col] = series.where(series.isin(allowed)) if allowed else series

# Drop canonical columns that ended up completely empty after filtering

return pd.DataFrame(out).dropna(axis=1, how="all")

Purpose:

This snippet shows the heart of the auditing logic—how the ETL pipeline turns the question inventories discovered during audits into strict, schema-validated data. It builds a whitelist of valid responses per question and filters raw survey data so only canonical questions and standardized values remain, producing a clean dataset that’s analytically reliable and comparable year after year.

After the audits establish a verified, canonical schema for every survey, the Transform stage turns those cleaned datasets into structured summaries ready for analysis, comparison, and visualization. This stage is where consistency, aggregation, and statistical clarity converge.

Each layer writes to data/processed/ so that every step can be resumed independently and verified in isolation.

2.1. Summarizing Raw Responses (summary_tables.py)

Once audit_map.py standardizes the columns and validates responses, summary_tables.py converts those cleaned files into frequency tables that quantify how often each response appears.

The script:

- Identifies which columns contain survey questions (and skips metadata like

School,Grade,Year,Tab). - Detects the response scale automatically, matching observed responses against known Likert or frequency patterns such as Agree / Disagree or All the time / Sometimes / Not at all.

- Counts and orders responses to preserve the logic of the original question.

def value_count_table(df, columns, scale_orders):

for col in columns:

values = df[col].dropna().unique()

# Infer which predefined scale (e.g., Agree/Disagree, Yes/No/Maybe, frequency) best matches the observed responses

scale_key, order = best_scale_match(values, scale_orders)

# Reorder counts to match the detected scale; if no scale matches, 'order' comes from sorted observed values

vc = df[col].value_counts().reindex(order, fill_value=0)

vc.name = col

all_summaries.append(vc)

# Each row = one question, each column = count of a response bucket

return pd.DataFrame(all_summaries)

Each question becomes a single row with numeric counts across categories, like:

| Question | Agree | Neither | Disagree |

|---|---|---|---|

| I feel safe at school. | 120 | 30 | 15 |

These are stored in data/processed/<cohort>/summary/.

2.2. Consolidating Across Response Variants (consolidate_responses.py)

Survey designs evolve from year to year. Sometimes the same concept is phrased differently or uses a slightly different scale. This script consolidates those variants by mapping them into unified “buckets.”

# Map different textual variants of frequency responses into a single, canonical bucket

frequency_map = {

"All the time": ["Every day", "All the time"],

"A lot of the time": ["Frequently", "A lot"],

"Sometimes": ["Occasionally", "Sometimes"],

"Not at all": ["Never", "Not at all"]

}

Each bucket combines variant responses into one consistent label. It also adds an Overarching column that connects each question to its broader analytic category, like “School Climate” or “Emotional Experience.”

The result is a consolidated, language-agnostic summary file (_consolidated_summary.csv) for each school year and cohort.

2.3. Aligning Questions Across Years (consolidate_questions.py)

Once each year’s responses are standardized, consolidate_questions.py merges them into a single, longitudinal dataset. Every canonical question is aligned across all academic years, ensuring that trends can be analyzed over time.

Key steps include:

- Standardizing and grouping by

Canonical Question. - Summing identical question totals within each year.

- Sorting responses by category order (for example,

Yes,Maybe,No).

# Combine all yearly files for this cohort into a single DataFrame

merged = pd.concat(frames, ignore_index=True)

# Label each question as Frequency, Yes/No/Maybe, Both, or Other, based on which buckets it uses

merged["Response Type"] = merged.apply(response_type, axis=1)

# Within each School Year, sort questions by response type and total volume for cleaner, more readable outputs

# (Pandas may warn about group_keys in future versions, but this pattern is correct here)

merged = merged.groupby("School Year").apply(

lambda g: sort_within_year(g, response_cols)

)

This produces clean multi-year tables such as:

| School Year | Canonical Question | Yes | Maybe | No | Overarching |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21-22 | I feel safe at school. | 210 | 30 | 10 | School Climate |

| 22-23 | I feel safe at school. | 198 | 45 | 8 | School Climate |

Each row represents a consistent, canonical question with comparable metrics over time.

2.4. Aggregating Across Cohorts (summarize_totals.py)

The final transformation stage merges the Younger and Older cohort datasets. It groups all canonical questions and sums their response counts across cohorts and school years.

# Combine Younger and Older cohorts into a single dataset

df_all = pd.concat([df_younger, df_older])

# Sum counts across cohorts for each canonical question to get program-wide totals

totals = df_all.groupby("Canonical Question")[response_cols].sum()

# Re-attach the Overarching category so each question can be rolled up into higher-level themes

totals = totals.merge(canon_to_over_df, on="Canonical Question")

The result is a single canonical_question_totals.csv file — the master dataset that underpins your dashboards and longitudinal reports. It captures the entire program’s survey history in one place.

The Transform Stage at a Glance

| Script | Function | Output |

|---|---|---|

raw_audit.py | Profiles questions and responses | SF_OA_*.csv |

audit_map.py | Cleans and enforces canonical mappings | <year>_<group>_ENGLISH_questions.csv |

summary_tables.py | Builds per-question frequency tables | _summary.csv |

consolidate_responses.py | Merges response variants into unified categories | _consolidated_summary.csv |

consolidate_questions.py | Aligns canonical questions across years | consolidated_questions_<group>.csv |

summarize_totals.py | Aggregates cohorts into a final master table | canonical_question_totals.csv |

Step 3: Load: Analytics-Ready Excel Outputs

At the end of the transformation chain, scripts/load/ consolidates every dataset into two major deliverables:

SF_Master_Data.xlsx— all cleaned survey responsesSF_Master_Summary.xlsx— executive-ready pivot summaries by year, question, and group

The Excel generation leverages xlsxwriter for performance and formatting consistency, so non-technical stakeholders can explore the data immediately without needing Python.

Jupyter Notebook: Pipeline Fundamentals

The accompanying Jupyter Notebook (etl_pipeline_demo.ipynb) demonstrates the core logic of all 10 ETL scripts — from extraction to Excel export — making it ideal for presentations, debugging, or onboarding new engineers.

Each notebook section corresponds to a specific stage:

scrape_drive_links.py

↓

load_feedback_data.py

↓

translate_spanish_csv.py

↓

raw_audit.py

↓

audit_map.py

↓

summary_tables.py

↓

consolidate_responses.py

↓

consolidate_questions.py

↓

summarize_totals.py

↓

load_to_excel.py

The notebook combines Python snippets, bash automation (run_etl.sh), and Markdown documentation, walking through:

- Google Drive API authentication

- CSV normalization

- YAML-based canonical mapping

- Summarization and consolidation logic

- Excel export and reporting

Each cell is fully annotated, offering readers a hands-on look at how each part of the ETL system functions in sequence.

The Makefile: Orchestrating Complexity with Simplicity

Instead of chaining bash commands, I used a Makefile to modularize the entire workflow.

| Command | Description |

|---|---|

make extract | Run API downloads & cleaning |

make transform | Run all mapping & consolidation steps |

make load | Build final Excel outputs |

make pipeline | Run everything sequentially |

make clean | Clear processed data outputs |

make test | Run all unit and integration tests |

This approach enforces discipline: every ETL stage is isolated, tested, and reusable.

It also aligns perfectly with CI/CD automation — GitHub Actions can invoke the same Make targets, ensuring parity between local and remote runs.

DevSecOps by Design

Security wasn’t an afterthought — it was foundational.

Practices integrated into the build:

.envmanagement for all secrets and keys- Linting and static analysis with Ruff, Flake8, and Black

- Security audits via Bandit and pip-audit

- Continuous Integration with GitHub Actions for automated testing and coverage reports

- A dedicated SECURITY.md outlining responsible disclosure policy

Every commit triggers linting, vulnerability scans, and test validation — merging only clean, tested code into main.

Lessons Learned

- YAML over hardcode. Separating configuration from logic makes the pipeline adaptable, safer to modify, and easier for non-developers to maintain. The YAML-driven design became the foundation for everything from source discovery to canonical mappings.

- APIs over manual downloads. Relying on the Google Drive and Sheets APIs ensured every ETL run was reproducible and up-to-date. Programmatic extraction eliminated the variability and risk of human workflows.

- GCP makes automation secure and scalable. Using a dedicated GCP project with service account authentication, IAM-scoped permissions, and cloud-managed API access allowed the extractor to run unattended while still being fully protected. This turned a fragile manual process into a reliable, cloud-backed data service.

- Logging is a superpower. Clear, structured logs across Extract, Transform, and Load steps enabled rapid debugging and transparent data lineage, even with large volumes of files.

- Data audits are non-negotiable. Audits provided the guardrails for data quality. They captured schema drift, surfaced question variations across years, and established the canonical blueprint that every transformation step depends on.

- DevSecOps elevates trust. Automated linting, testing, dependency scanning, and credential hygiene transformed the project from a script into an enterprise-ready pipeline.

- Makefiles matter. Makefiles unified the local and CI experience, providing a reproducible command interface for running each stage of the ETL independently or as a full pipeline.

Why It Matters: The Bigger Picture

The Transform stage is where raw survey data becomes usable evidence. This part of the pipeline matters because it ensures that:

- Every question contributes to a consistent analytical story, even if its wording, translation, or response scale changed across years.

- Each transformation step is isolated, reproducible, and auditable, so every number in the final dataset can be traced back to its original tab.

- Cross-year comparability is preserved, enabling accurate longitudinal insights rather than one-off snapshots.

- Unexpected responses, schema drift, and malformed data are caught early, rather than silently corrupting downstream summaries.

Beyond the mechanics, the pipeline reflects the broader engineering philosophy behind the entire project:

- Automation over manual processes: API-driven extraction prevents errors and keeps the pipeline aligned with the current Drive structure.

- Configuration over hardcoding: YAML centralizes canonical mappings, scales, and extraction logic so updates require no code changes.

- Cloud identity over human authentication: A GCP service account enforces permissions, security, and reproducibility.

- Documentation over ambiguity: Audits produce transparent artifacts that explain exactly how each survey transformed into its final form.

These principles extend well beyond this project. They now guide how I design all my ETL systems, from NYC InfoHub scrapers to NOAA environmental pipelines:

- Automate where possible

- Parameterize everything

- Secure by design

- Document every step

This project demonstrates how clean data and clean code reinforce one another — and how a well-designed pipeline becomes a scalable template rather than a one-off script.

Developed by Dylan Picart as a Data Analytics Engineer at Partnership With Children

GitHub: GitHub